Sculpture Garden

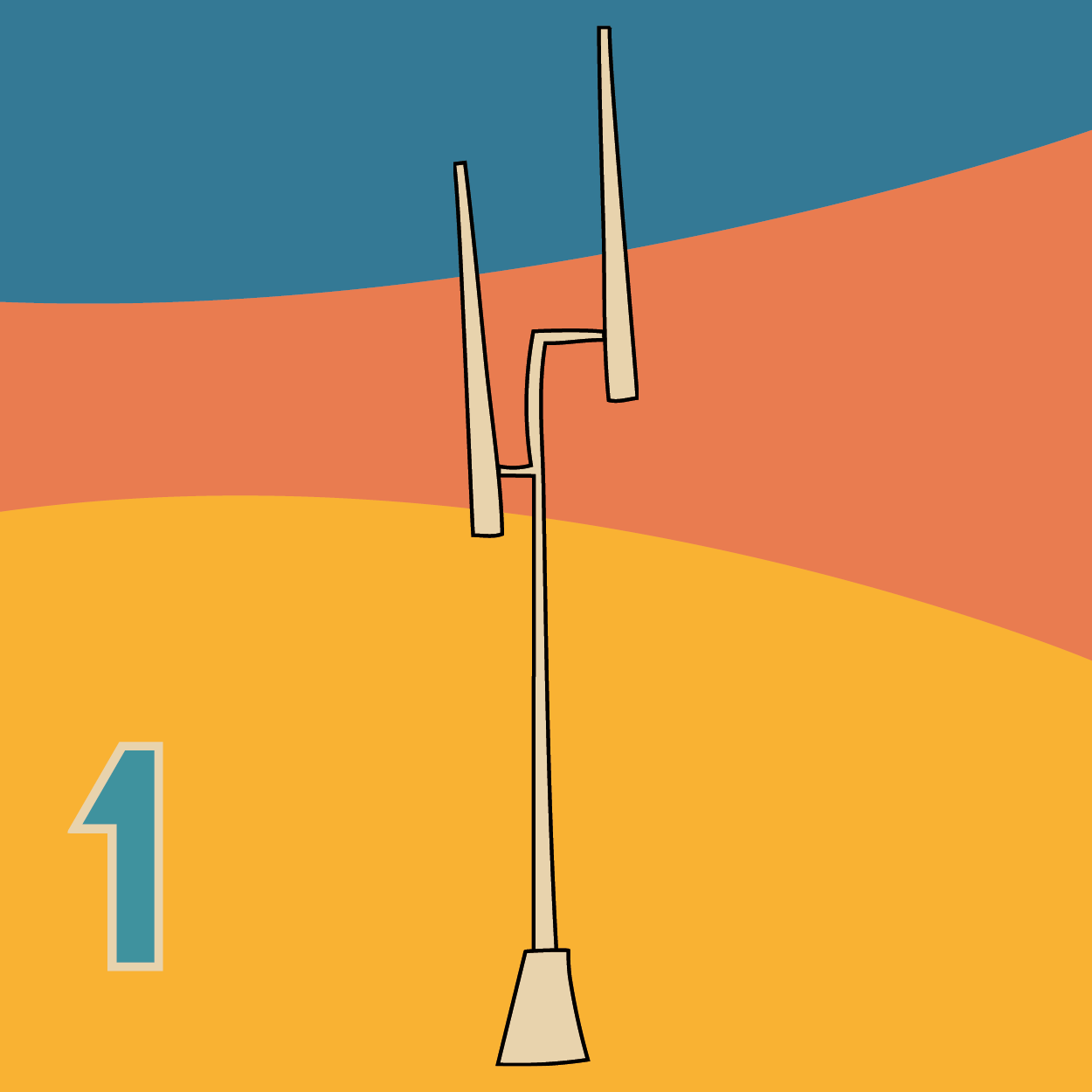

George Rickey (1907-2002) formed a career with what he referred to as “useless machines.” These machines, carefully calibrated kinetic sculptures made of stainless steel, sway intermittently with the currents. Clock hands in the wind, Rickey’s Two Lines Up-Spread mark the passing of time like a pendulum pulsing to the day. The son of an engineer and the grandson of a clockmaker, Rickey’s pursuit of first, painting and second, kinetic sculpture are not without nod to his family’s history of tinkering with cogs, creating movement. Movement became the movement of his career. His steel, wind-driven formations described by TIME Magazine as, “Curiously moving metal sculptures that gambol and gimbal in the wind.”

George Rickey, Two Lines Up-Spread, 1971, Stainless steel, H: 384 inches, Gift of the LBMA Museum Association 1971

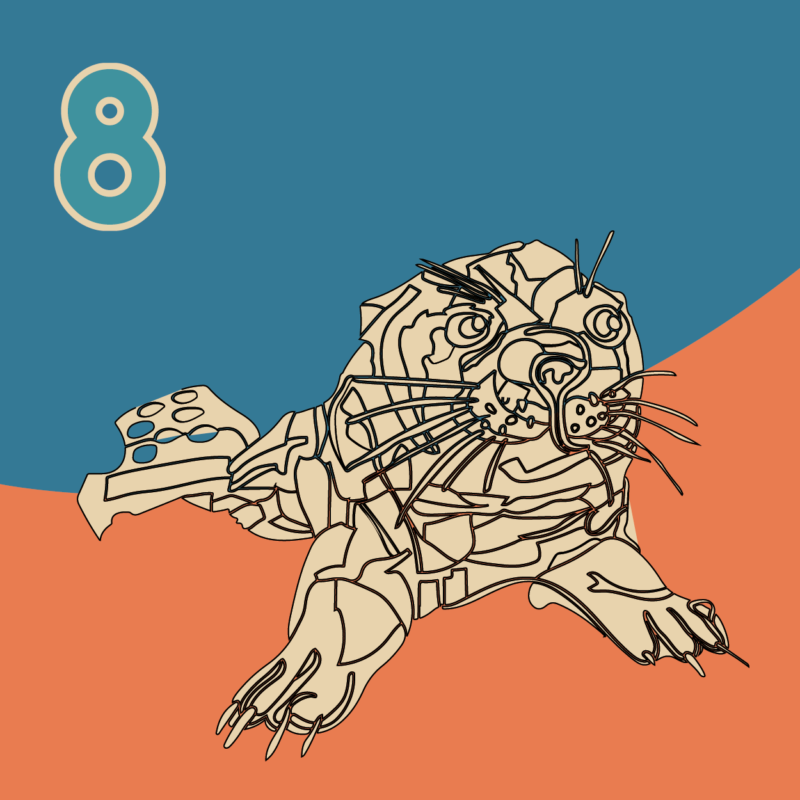

Claire Falkenstein (1908-1997) developed an artistic vocabulary of her own. Throughout her life, continuity and change, space and matter, and junctures between moving points laid the backdrop for each exploration, each commission. One of the most important figures in post-war American art, she created “living” artworks—lines, points, and objects appearing to exist in continuum through space. The Point as a Set #16 is part of a larger series that marked a pivotal shift in Falkenstein’s artistic career. This series, varying in expression “from happy, open, curving lyricism to ominous, closed, hard-edged density,” noted Falkenstein in a statement to the Tate Gallery in 1981, refer to mathematics and in tandem, a connection to the natural world. The Point as a Set #16 was purchased by the LBMA Museum Association and unveiled to the public on Wednesday, June 16, 1965.

The Point as a Set #16, 1965, Copper tubing and venetian glass, H: 36 W: 36 Diam: 36 inches, Gift of the LBMA Museum Association 1965